What makes one choice preferable to another? Why do anything at all? These are the questions of ethics, and they all hinge on the notion of what is valuable, or, more simply, good. We make the choice we have evaluated to achieve more good—to be better—than the alternative; we do things because they are good and refrain from doing things that are not good. Hence, the ultimate question of ethics: what is the good, that toward which all goodness is aimed? We take countless actions every day, most of which seem to be means to some other end, so what could that ultimate end actually be?

Spinoza offers a famous, and somewhat notorious, proposition for this ultimate ethical principle. He wrote it in Latin, so it’s come to be known by the Latin word at the heart of the principle: the conatus doctrine. It states that it is the fundamental nature of any being to strive (this is the usual English translation of conatus) for the preservation of its being. Critics claim that this proposition is inadequately argued—basically just stated as a self-evident truth—and that, while it may have a kind of common sense, it is far from true by definition. Part of the latter claim is that the conatus doctrine is (apparently) psychological. After all, what would it mean for, say, a rock to strive to persist in its own being? Spinoza must therefore be talking about organisms with volitions and desires, which is far removed from talking about fundamental truths about being. Self-preservation may be a kind of default behavior, but in the end it is just a possible (albeit very common) choice that a being can make, and there seem to be plenty of examples of human beings choosing not to preserve their own being, either through self-sacrifice or suicide.

It is true that Spinoza does not offer much in the way of argumentation for the conatus doctrine, but its meaning can be better understood if we keep in mind that Spinoza is almost fanatical in his reduction of everything to ontology, i.e. the study of the nature of being. For him, everything psychological or ethical must ultimately be explained in terms of what something is. So when he says that being a thing is immediately, i.e. the very same as, the imperative to preserve itself, he is not making a psychological claim about some kinds of beings, but rather a statement about being anything at all. In short, Spinoza knows what he’s saying: his argument is ontological, not psychological. So how can he respond to the apparently obvious counterexamples of suicide or the absurd self-striving rock?

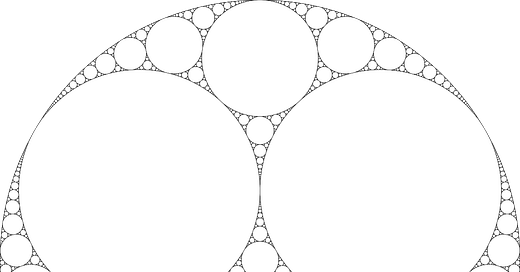

Recall from our discussion over the last few weeks that what something positively is can only be grasped in negative contrast to something else: “this” only means something if there’s a “that,” otherwise everything is a “this.” What we’re describing here is, in fact, the conatus doctrine: to be one thing is to immediately resist being something else. Without this negativity, this difference, this resistance, it is not possible to positively be anything. Thus, to be and to resist non-being is one and the same thing. The mistake is thinking that any particular thing can have a being independent of its negative interrelations with other things, to believe that objects can ever be free-standing or just somehow “floating” in space independent of one another. This is the mistake of the mode of thought called “the understanding,” which can only think of objects as separate and unrelated and which confuses its own divisive activity with a reality it imagines to be outside itself. Again, objects are their relations with one another; the differences between them created by the understanding are only necessary to make these relations possible. Otherwise, there would be no difference and therefore no beings.

This might be sufficient to explain how a rock can “strive” to preserve itself: being a rock is the same as being not not a rock—no mind necessary. It wouldn’t be much of a rock if it spontaneously turned into, say, air. We can also think about this in terms of chemistry: it’s relatively easy to smash a rock into smaller rocks, but to make the rock something else requires massive amounts of energy. That energy is required to overcome the “striving” of the rock to remain a rock.

But what about self-sacrifice and suicide? What are we to make of an apparently self-annihilating being? We have to ask ourselves: what is being annihilated, and what is performing the annihilation? A rock may be just a rock, but what are we, actually? I think it’s safe to say that we are not merely our bodies, simply from our ability to distinguish between “me” and “my body.” Rather, our identity appears to be fluid, mysteriously expanding and contracting according to the situation, and self-sacrifice and suicide are the two poles of a spectrum of identity. With self-sacrifice, I demonstrate that my self-concept is greater than the limits of my individual consciousness; with suicide, I demonstrate that my self-concept is nothing but my individual consciousness—not my body, nor anything in the world that might give that consciousness substance and allow it to be consciousness of anything. With suicide, I demonstrate that I am nothing but a consciousness that desires total oblivion. But in doing so, I do not really destroy myself; rather, I destroy that which torments myself, even if that leaves myself totally empty. As I’ve argued before, there is no action without reason, and reasons always flow from self interest. Thus, action is only ever in service of some kind of self, and truly attempting to destroy oneself is a contradiction.

The conatus doctrine stands. To be anything is to strive to continue being that thing, because the conatus doctrine amounts to an ethics of self-expression, an ethics that is an ontology and an ontology that is an ethics. Your being and your actions are one. But to be human is to have a breadth of possible identities that, say, rocks do not. It is therefore essential to do the work of understanding what we are, because all of our actions are an immediate extension of that self-concept. If I really am nothing more than myself, or myself and whomever shares my blood or nationality or whatever, that is, if I am only on one side of the line between self and other, then I will try to preserve that self by resisting the other and taking from it. This is the ethics of competition and mutual hostility that flows immediately from the worldview of pure difference, and which in turn developed over time into the capitalist world we inhabit today.

If, however, I recognize that what I negatively define myself against also positively defines me, if I see not only my difference but my substance in the other, then I will have grasped a concept of self that transcends its difference from the other. This is the realization that everything is merely self-different, and an entirely different ethics flows from it, not one of competition but rather of cooperation and symbiosis. This is not a contradiction of the conatus doctrine of self-preservation, but rather the only true means of its fulfillment. We know all too well that the ethics of competition leads to exploitation of humanity and nature, as well as both literal and metaphorical arms races that drive that exploitation forward exponentially. And perhaps there may be some short term solution to the symptoms of this vicious cycle—maybe a technological fix for some of the byproducts of our industrial explosion—but there can never be an ultimate fix for all of them. This is because our entire civilization is a manifestation of this infinite arms race logic, and there is no way it can end other than collapse.

That is, unless we overcome our purely negative self-concept and embrace the fuller understanding of self and other as mutually essential. When we do, we will stop this infinite deferment of value into the future, this infinite, empty striving to be stronger and better. Instead, we will become the actually infinite, an end unto itself, perfect as we are and lacking nothing. This is, in fact, already the case; we just don’t realize it.